Leftover wine is a sin”, goes the old dinner party cliche. And if that’s the case, then France – surely the most oenophilic nation of all – is in for an eternity of hellfire. Faced with an enormous surplus of wine, the French government is pouring away millions of litres of the stuff and uprooting vineyards – in a move agriculture minister Marc Fesneau claims is “aimed at stopping prices collapsing, and so that winemakers can find sources of revenue again”.

As a product that commands hefty mark-ups and never seems to go out of fashion, you might assume that wine was an evergreen cash cow for the French. But this spate of stock destruction is actually a symptom of an industry that is suffering. The CIVB, a trade group which lobbies for wine producers in the Bordeaux region, has warned that some growers are in “great economic difficulty”, and in December, there were large protests on the streets of Bordeaux, with tractors blocking roads in demand of government aid.

To date, the French government has spent around €200 million getting rid of excess wine, with red the most affected, and unprofitable vineyards, while there have been similarly large sums spent by the EU. In turn, much of the wine is being converted into sanitising gels and biofuel products. “The problem is that making wine isn’t like brewing beer, whereby you can suddenly just halt production. There’s a whole infrastructure that is hard to stop once you start,” reveals one insider.

There are two tiers of explanation for the wine glut, the first being complex, environmental and geopolitical. There is the rapid de-investment of Chinese money in the market, which kept many vineyards afloat for years. There’s climate change, deadly mildew, the endless Covid aftershocks, a shortfall of migrant workers and exportation difficulties. It should also be said that tearing up vineyards and chucking away wine is nothing new in France, and Australia has seen similar issues in recent years.

But where matters get worrying for producers is how these production issues collide with a wider shift in drinking habits. The European Commission estimates that wine consumption has fallen 7 per cent in Italy, 10 per cent in Spain, 15 per cent in France and 22 per cent in Germany. Meanwhile, wine production is actually increasing, leading to the kind of crippling oversupply that is fuelling the problems in Bordeaux.

“Much of the French wine industry is based on a kind of everyday consumption that has collapsed, says Richard Halstead, from drinks market analysts IWSR. “The French still drink approximately twice the amount of wine compared to the Brits on a per capita basis. But the thing is, they used to drink even more.”

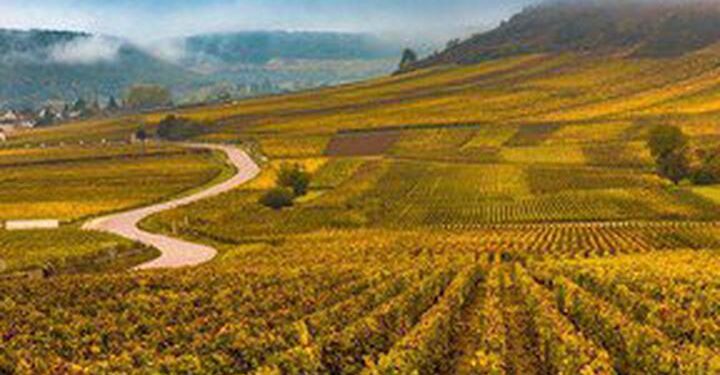

The onus here is not on the Châteauneuf-du-Papes, Pétruses or Dom Pérignons, but the reliable plonk that the French are notoriously good at. “The stuff that’s being ripped out of the ground and repurposed is what we’d call ‘bulk wine’,” says Sam Hancock, a wine distributor. “But when it comes to regions like Burgundy, the classified growers, they can’t make enough to supply the demand … it’s still the top market.”

Despite our reputation for vino-philistinism, you can see similar trends in the UK: “Some big importers to the UK had to destroy a hell of a lot of wine, because they weren’t selling hundreds of cases a week to hotels, function centres – the kinds of places that go through more average kinds of wine,” says Joshua Castle, head sommelier at London restaurant Noble Rot.

But it isn’t all just changing tastes. According to market analysts Wine Intelligence, the number of regular wine drinkers in the UK is declining, falling by four million in the past five years (to 26 million regular wine drinkers). Then there’s a demographic and taste shift going on, with only 26 per cent of 18- to 34-year-olds regular wine drinkers, and many teetotal.

Ashley Tuiri, a buyer and manager at Ricardo’s Cellar, a bottle shop/bar in West London, sees this phenomenon first hand: “Most of the young people we get in go for beer and spirits, and if they do drink wine, it will tend to be rosé or sparkling. A lot of them have been influenced by the fitness industry so they often go for a soft drink, or something low calorie.”

Then, there is the power of choice. Once upon a time, wine (and French wine in particular) was the be all and end all of quality drinking. Now, people in want of social lubrication are presented with a wealth of options, ranging from craft beers to artisan spirits, cocktails, low/no-alcohol versions of classics and the entire gamut of soft drinks.

Yet established drinkers, too, are also moving away from old habits. “ ‘Aperitif hour’ is now quite dominated by drinks other than wine,” says The Telegraph’s wine columnist Susy Atkins. “You see people with the ubiquitous Aperol Spritz, the big G&T. There’s more variety, people don’t feel constrained by one type of drink, the ‘what’s your poison?’ mindset.”

Halstead adds: “The idea of drinking at high intensity, or high frequency, has fallen out of fashion. You don’t have to be a whizz mathematician to work it out: if there’s more choice, and less is actually being consumed overall, the traditional wine-drinking market is going to suffer.”

Even within wine itself, the market is diversifying old prejudices like “dusty and French equals best”. Hancock says that over lockdown people learned more about wine and became more adventurous. Many vendors point to products like natural wine and, in the UK, the rise of English sparkling wine.

French wines can be forbiddingly expensive, and here, new markets step in: “A lot of people are seeking better quality and value,” says Tuiri.

I also wonder if there are also changes in what people want, or don’t want out of drinking. I’ve always found that full-bodied (mostly French, also Italian) reds produce a particular kind of drunkness. One that I’m not too keen to step into; heavy-headed, crimson-faced, slightly “funky”. Polling friends, few seem to regularly drink reds; one even had to stop drinking the stuff with his partner at dinner, referring to it as “argument juice”.

Those few percentage points can mean the difference between a great evening and a terrible morning. “People have become a lot more concerned with ABV levels. Before, if people wanted to drink a Merlot, they’d just drink a Merlot. Now they’re saying ‘oh 14 per cent, that’s a bit much’, says Tuiri’s colleague Ricardo Garcia.

There is one wine that is on the ascendancy: rosé. Long derided as being too cheap, naff, and altogether too easy, the pink stuff is booming, with Sainsbury’s declaring sales are up 26 per cent year on year. “It’s a more accessible drink”, says the wine insider I spoke to. “It’s the kind of up-tempo drink you can have with your friends in the garden. It looks nice in an Instagram picture. Whereas red wine is a more acquired taste.”

Despite all the pessimism, almost everyone I spoke to was certain that the high end would always be dominated by French offerings. “There’s still a cache about the revered bordeaux, burgundies,” says Atkins. “It’s maybe in the lower end of the price range that France can struggle against the diverse competition. But there’s still exciting wines coming out of France.”

So there may be some hope for your old-school French table wines – your Chateaux De Antifreezes; the kind we’re told make French schoolchildren such great conversationalists and so respectful of their elders. The drinks industry is always trying to ignite trends, and stranger things have ended up in fashion. But the next time around perhaps we’re more likely to reach for that zero-alcohol spritzer afterwards, rather than the second bottle.

Discussion about this post